8. Fine-tuning mathematical formulas | LaTeX manual

We have already discussed most of the facilities needed to construct math formulas. But there are still some fine points that will let you produce really beautiful formulas, the formulas that will improve the overall appearance and readability of the books and papers that you would type.

8.1. Punctuation

The general rule is: when a formula is followed by a period, comma, semicolon, colon, question mark, exclamation point, etc., put the punctuation after the $, when the formula is in the text; but put the punctuation before the $$ when the formula is displayed. For example,

1If $x<0$, we have shown that $$y=f(x).$$So, you shouldn’t ever type anything like

1for $x = a, b$, or $c$.It should be

1for $x = a$, $b$, $c$.In the first case, TeX will typeset $x = a, b$ as a single formula, thus putting a thin space between the comma and the b. This space will not be the same as the space between the comma and c, since spaces between words are always bigger than thin spaces. Such spacing looks bad, but in the second case the spacing will look good.

It’s also important that TeX will never break a line of a paragraph at the space between the comma and the b because breaks after commas in formulas are usually wrong as in the equation $x = f(x, a)$. Thus, the possibility of breaking lines in a paragraph gets inhibited which leads to a worse appearance of the typeset document. In other words, if a punctuation mark belongs linguistically to the sentence rather than to the formula, leave it outside the $’s.

8.2. Non-italic letters

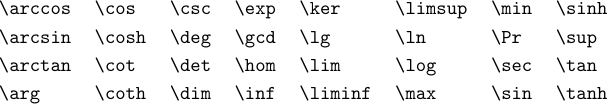

Common math functions like “log” are always set in Roman type. The best way to include such objects in a formula is to make use of the following commands:

In the following examples some of these commands are used:

The last two displayed formulas show that some of the commands are treated by TeX as large operators with limits like the summation sign. And the subscript on \max is not treated like the subscript on \log. Subscripts and superscripts will become limits when they are attached to \det, \gcd, \inf, \lim, \liminf, \limsup, \max, \min, \Pr, and \sup, in display style.

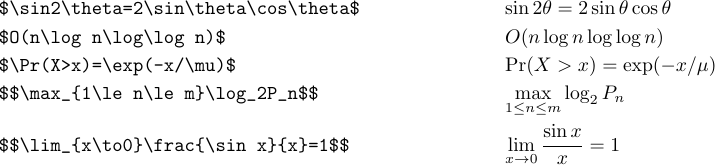

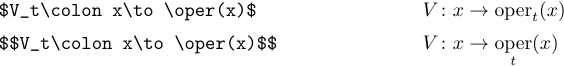

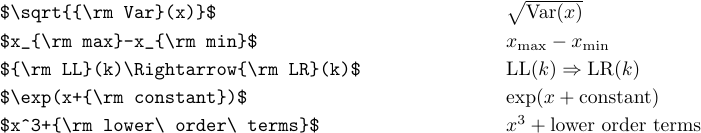

If you need Roman type for a frequently used function or operator that is not listed above, you can easily define your own command. Suppose you want to define an operator with limits and call it \oper. To do so, you must include the following definition in the preamble:

1\def\oper{\mathop{\rm oper}}

In case your operator isn’t supposed to have limits, use a definition like the following:

1\def\oper{\mathop{\rm oper}\nolimits}If you need Roman type just for a single use, it’s easier to switch to \rm type as follows:

Notice the uses of ‘\ ’ in the last case. Without them, ordinary blank spaces would have been ignored and lower order terms would have been typeset as “lowerorderterms”.

The word “mod”, which is also generally set in Roman type in formulas, needs more care, because it is used in two different ways. LaTeX provides the \bmod command to be used when “mod” is a binary operation and the \pmod command to be used when “mod” occurs in parentheses at the end of a formula.

Notice that \pmod inserts its own parentheses; the quantity that appears after “mod” in that parentheses should be enclosed in braces unless it is a single symbol.

You can also get other styles of type the same way you get Roman type by using \rm. For example, \bf gives boldface:

You can notice that the ‘+’ and ‘=’ are still in Roman type. LaTeX sets things up so that commands like \rm and \bf affect only the uppercase letters A to Z, the lowercase letters a to z, the digits 0 to 9, the uppercase Greek letters \Gamma to \Omega, and math accents like \hat and \tilde. Incidentally, no braces were used in this example, since $’s have the effect of grouping; \bf changes the current font, but the change is local, so it doesn’t affect the font that was current outside the formula.

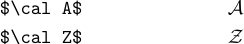

You can also say \cal in formulas to get uppercase letters in a “calligraphic” style.

This works only with the letters

AtoZ; you’ll get weird results if you apply\calto lowercase or Greek letters.

There’s also \mit, which stands for “math italic”. This affects uppercase Greek.

When \mit is in effect, the ordinary letters A to Z and a to z are not changed; they are set in italics as usual, because they ordinarily come from the math italic font. Conversely, uppercase Greek letters and math accents are not affected by \rm, since they ordinarily come from the Roman font.

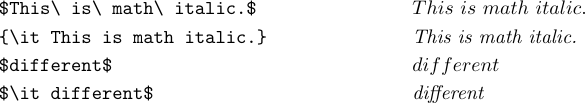

With LaTeX, you can also type \it or \tt to get text italic or typewriter letters in your formula. You probably wonder why both \mit and \it are provided. The answer is that \mit is “math italic” (which is usually best for formulas), and \it is “text italic” (which is usually best for running text).

The math italic letters are wider, and the spacing is different. This works better in most formulas, but the appearance suffers when you try to type certain italic words like “different” in math mode. A wide italic ‘f’ is usually desirable in formulas, but not in text. Therefore, it’s best to use \it in a formula that is supposed to contain an actual italic word. This is usually not a case of classical mathematics, but it is a common case when computer programs are being typeset:

The second example shows the use of short underlines to break up identifier names.

8.3. Spacing between formulas

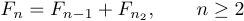

It is a common case when a display contains more than one formula; for example, an equation may be accompanied by a side condition:

In such cases you need to tell TeX how much space to put after the comma, because normal conventions would bunch things together. To get this, you can type

1$$F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2},\qquad n\ge2$$.Here, \qquad stands for “double quad”, where “quad” means some amount of space that is common for printers. Thus \quad means a printer’s quad of space in the horizontal direction. Whenever you want spacing that differs from the normal conventions, you must specify it explicitly by using commands such as \quad and \qquad.

A quad used to be a square piece of blank type, 1em wide and 1em tall - approximately the size of a capital M; but LaTeX’s quad has no height.

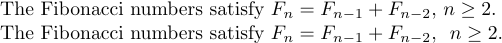

In the text of a paragraph, formulas look better if they are separated by words, not just by commas. But if there really is no text to insert, you should at least put some space between the formulas. Compare

1The Fibonacci numbers satisfy $F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}$, $n\ge2$.and

1The Fibonacci numbers satisfy $F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}$, \ $n\ge2$.which give

The ‘\ ’ here gives a visual separation that partly compensates for the bad style.

8.4. Spacing within formulas

We have already seen that TeX does automatic spacing of math formulas which makes them look right in most cases. However, it’s natural that exceptions arise, since the number of possible formulas is enormous, and TeX’s spacing rules are quite simple. So, it is desirable to have fine units of spacing for such cases, instead of the big pieces that arise from \ , \quad, and \qquad.

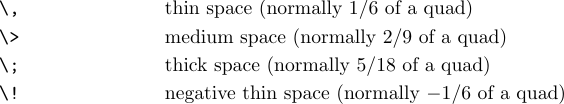

The basic elements of space that TeX puts into formulas are called thin spaces, medium spaces, and thick spaces. TeX inserts them into formulas automatically, but you can add your own spacing whenever you want to, by using the commands

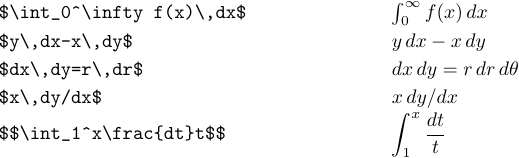

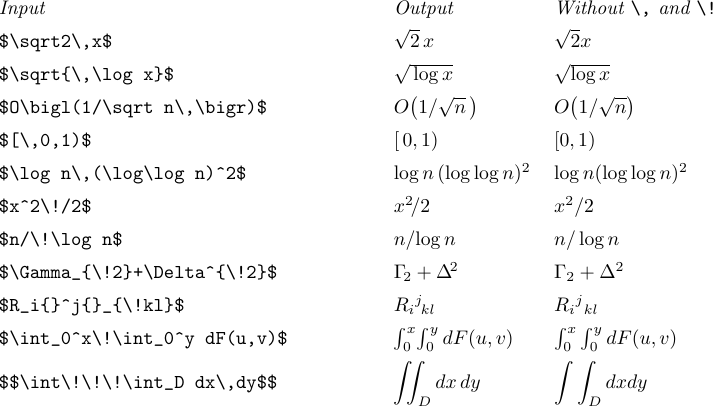

Formulas involving calculus look best when an extra thin space is inserted before dx or dy or d whatever; but TeX doesn’t do this automatically. The following examples show how to tell TeX about these needs:

Notice that no \, was needed after the ‘/’ in the second last formula. There is also no need for \, in the last example, since the dt appears all by itself in the numerator of a fraction; this detaches it visually from the rest of the formula.

Physical units, when they appear in a formula, should be set in Roman type and separated from the preceding material by a thin space:

Thin spaces should also be inserted after exclamation points (factorial operation), if the next character is a letter or a digit or an opening delimiter:

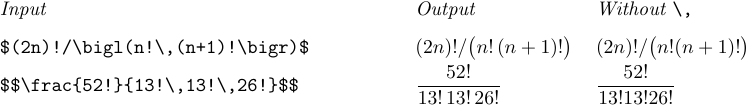

Besides these cases, you will occasionally encounter formulas in which the symbols are bunched up too tightly, or where too much white space appears, because of certain unlucky combinations of shapes. A tastefully applied \, or \! will open things up or close things together so that the reader will not be distracted from the mathematical significance of the formula. Radicals and multiple integrals are often candidates for such fine tuning. Here are some examples of situations to look out for:

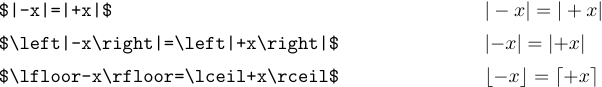

TeX’s spacing rules sometimes fail when ‘|’ and ‘\|’ appear in a formula, because these symbols are treated as ordinary symbols instead of as delimiters. Consider the formulas

In the first case the spacing is wrong because TeX thinks that the plus sign is computing the sum of ‘|’ and ‘x’. The use of \left and \right in the second example puts TeX on the right track. The third example shows that no such corrections are needed with other delimiters, because TeX knows whether they are openings or closings.

8.5. Ellipses

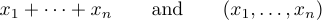

An ellipsis can be indicated by two different kinds of dots, one higher than the other. The best traditions distinguish between these two possibilities. It is generally correct to produce formulas like

but wrong to produce formulas like

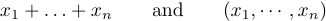

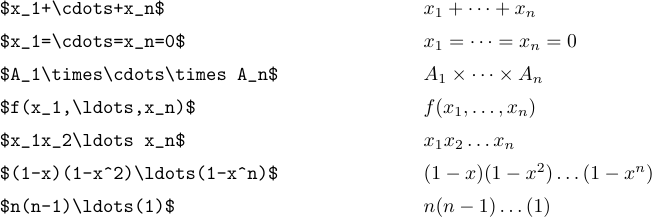

The idea is to type \ldots when you want three low dots, and \cdots when you want three vertically centered dots. In general, it’s best to use \cdots between + and - and multiplication signs, and also between = signs or “less-than-or-equals” signs or subset signs or other similar relations. Low dots are used between commas, and when things are juxtaposed with no signs between them at all:

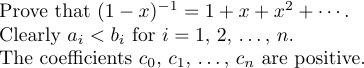

But there’s a special case in which \ldots and \cdots don’t produce the right spacing. This happens when they appear at the very end of a formula or just before a closing delimiter. In such situations an extra thin space is needed. For example, consider the following sentences:

The first sentence is produced by typing

1Prove that $(1-x)^{-1}=1+x+x^2+\cdots\,$.Without the \, the period would have come too close to the \cdots.

The second sentence was typed as:

1Clearly $a_i<b_i$ for $i=1$,~2, $\ldots\,$,~$n$.Notice the use of ties (~), which prevent bad line breaks. Such ellipses are very common in some forms of mathematical writing, so LaTeX provides the \dots macro as an abbreviation for $\ldots\,$ to use in the text of a paragraph. The third sentence can therefore be typed

1The coefficients $c_0$, $c_1$, \dots, ~$c_n$ are positive.8.6. Line breaking

When you have formulas in a paragraph, TeX may have to break them between lines. It will break a formula only after a relation symbol, or after a binary operation symbol, where the relation or binary operation is on the outer level of the formula, which means not enclosed in {...}. For example, if you type

1$f(x,y) = x^2-y^2 = (x+y)(x-y)$in the middle of the paragraph, there is a chance that TeX will break after either of the = signs (preferred) or after the - or + or - (in an emergency). But there won’t be a break after the comma in any case, since commas after which breaks are desirable shouldn’t appear between $’s.

It you don’t want to allow breaking in this example except after the = signs, you could type

1$f(x,y) = {x^2-y^2} = {(x+y)(x-y)}$because these additional braces “freeze” the subformulas, putting them into unbreakable boxes. But there’s no need to worry about such things unless TeX actually breaks a formula badly, since the possibility of this is pretty low.

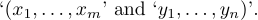

If you do want to allow breaking at some point in the outer level of a formula, you can say \allowbreak. For example, if the formula

1$(x_1,\ldots,x_m,\allowbreak y_1,\ldots,y_n)$appears in the text of a paragraph, TeX will allow it to be broken into two pieces

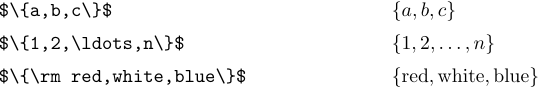

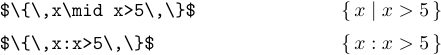

8.7. Braces

The symbols ‘{’ and ‘}’ are used in a number of different notations, and LaTeX provides some commands to help you cope with formulas involving such things. The simplest case is when braces are used to indicate a set of elements. For example, “{a, b, c}” stands for the set of three elements a, b, and c:

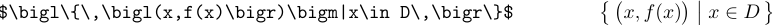

A set may also be indicated by giving a generic element followed by a specific condition. For example, the set of all objects x that are greater than 5 can be written as follows:

These are two variants to indicate the same set. The first one requires using \mid to get the vertical bar, while the second one doesn’t require anything except the colon, which is treated as a binary operation.

When the delimiters get larger, they should be called \bigl, \bigm, and \bigr:

Formulas with even larger delimiters would use \Big or \bigg or even \Bigg commands.

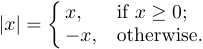

You may also find another use of braces in displayed formulas. It’s actually one left brace that indicates a choice between a number of alternatives:

This construction can be typed using the command \case:

1$$|x|=\case{x,&if $x\ge0$;\cr

2 -x,&otherwise.\cr}$$Each of the cases has two parts separated by the & symbol, which plays a special role in building tabular structures. To the left of the & is a math formula that is implicitly enclosed in $...$; to the right of the & is ordinary text. So -x, in the second line will be typeset in math mode, but the otherwise will be typeset in horizontal mode. Blank spaces before and after the & are ignored. There can be any number of cases, although usually there are just two. Each case should be followed by \cr.

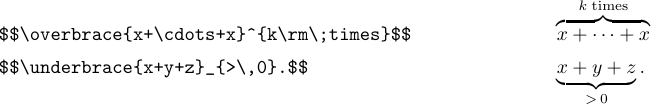

Horizontal braces will be set over or under parts of a displayed formula if you use the commands \overbrace or \underbrace. Such things are considered to be large operators like \sum, so you can put limits above or below them by specifying superscripts or subscripts:

8.8. Matrices

Matrices are fairly common objects in math formulas; they are just rectangular arrays of formulas that are arranged in rows and columns. LaTeX provides the \matrix command to deal with the most common types of matrices.

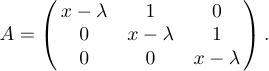

For example, suppose that you want to specify the display

All you do is type

1$$A=\left(\matrix{x-\lambda&1&0\cr

2 0&x-\lambda&1\cr

3 0&0&x-\lambda\cr}\right).$$This is quite similar to the \cases construction we looked at earlier; each row of the matrix is follower by \cr, and & signs are used between the individual entries of each row. However, unlike in \cases, you are supposed to put your own \left and \right delimiters around the matrix. The reason is that different delimiters may be used in different matrix constructions. On the other hand, parentheses are used more often than other delimiters, so you can type \pmatrix if you want LaTeX to set the parentheses for you:

1$$\pmatrix{x-\lambda&...&x-\lambda\cr}.$$Each entry of a matrix is normally centered in its column, and each column expands as much as necessary to accommodate the entries it contains, and there is a quad of space between columns. If you want something to come out flush left/right in its column, follow/precede it by \hfill.

Each entry of a matrix is processed separately from the others, and it is typeset as a math formula in text style. Thus, for example, if you say \rm in one entry, it does not affect the others. Saying {\rm x&y} is invalid.

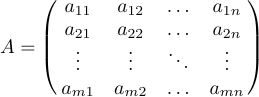

Matrices often appear as generic patterns that use ellipses to indicate rows or columns that are left out. You can typeset such matrices by putting the ellipses into their own rows and/or columns. In addition to \ldots, LaTeX provides \vdots (vertical dots) and \ddots (diagonal dots) for such constructions. Consider the following matrix

that is specified as:

1$$A=\pmatrix{a_{11}&a_{12}&\ldots&a_{1n}\cr

2 a_{21}&a_{22}&\ldots&a_{2n}\cr

3 \vdots&\vdots&\ddots&\vdots\cr

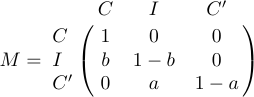

4 a_{m1}&a_{m2}&\ldots&a_{mn}\cr}$$Sometimes a matrix is bordered at the top and left by formulas that give labels to the rows and columns. For this situation, a special macro called \bordermatrix is defined in LaTeX. For example, the display

is obtained when you type

1$$M=\bordermatrix{&C&I&C'\cr

2 C&1&0&0\cr

3 I&b&1-b&0\cr

4 C'&0&a&1-a\cr}$$The first row gives the upper labels, which appear above the big left and right parentheses; the first column gives the left labels, which are typeset flush left, just before the matrix itself. The element at the intersection of the first column and the first row is normally blank. And like \pmatrix, \bordermatrix inserts its own parentheses.

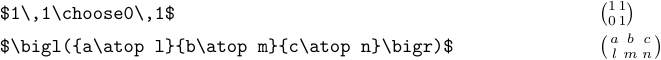

Putting matrices into the text of a paragraph is usually inadvisable. The reason is that they are so big that they are better displayed. But still, you may occasionally want to neglect this. In this case, you can use \choose or \atop:

The \matrix macro doesn’t produce small arrays like this.